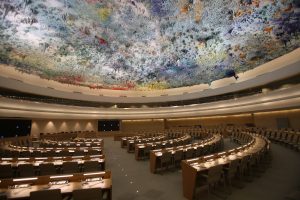

REFLECTION The past few weeks, the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) held meetings in Geneva. Since its establishment in 2006, the Council has been a contentious institution. The lawyer Sara Bengtson situates one of the main criticisms against the HRC – that its lack of formal membership criteria prevents it from effectively promoting human rights – in the context of a broader philosophical discussion of how liberal states should organize their international relations.

(En sammanfattning av denna artikel på svenska finns här.)

The Human Rights Council is the main inter-governmental body within the UN system responsible for the protection of human rights. The Council’s work spans from speaking out on human rights situations in specific countries, examining individual complaints and appointing independent rapporteurs who monitor thematic human rights issues, to the peer review Universal Periodic Review (UPR).

Every third year, the UN General Assembly votes on who should fill the 47 seats of the Council, which are open to all UN member states. The lack of further formal criteria has been a cause of criticism. In Sweden, representatives of the Liberal Party have voiced demands on the dissolution of the Council. The US has been its most vocal critic on the global stage. This past June, the Trump-administration announced its withdrawalfrom the Council. Observers interpreted this as a sign of resignation from multilateralism and global leadership on human rights.

According to the US government, the decision to withdraw was in part due to the lack of membership criteria. “Look at the Council membership,” UN ambassador Nikki Haley said, “and you see an appalling disrespect for the most basic human rights.” With non-democracies as members, few could disagree. More complex however is the question of whether this motivates liberal democracies’ withdrawal from, and, ultimately, the dissolution of the Council.

International society as a liberal federation

The question of how liberal democracies should arrange their international relations is an old one. In 1795, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) published Perpetual Peace. Kant’s peace is achieved through the signing of an imaginary treaty, whereby states undertake to be republican, or liberal. Through representation and separation of powers, states will hesitate to start wars. They will signal to other states that they are able to make credible commitments, as rash acts and exposed bluffs will lead to electoral defeats. Republics may credibly join the world federation, a formal commitment to peace, to which cosmopolitan law, or economic interdependence, adds material incentives. Taken together, republicanism, the world federation and cosmopolitan law create a self-enforcing peace.

In his book Ways of War and Peace (1996), Michael W. Doyle, professor of international relations at Columbia University, examines the liberal peace and suggests that it indeed exists. Importantly, however, liberals have fought numerous wars with non-liberals; sometimes defensive, sometimes aggressive or imperialist. Whereas liberals trust other liberals because of their liberalism, they distrust non-liberals because of their lack thereof. Liberals may thus enter into sporadic agreements with non-liberals, but in the absence of trust, and enforcement, the prospects of lasting international cooperation are low. For the universally inclined, the liberal federation is accordingly not effective.

Adjusting the boundaries of the liberal federation

Whereas Kant restricts the international society of states to liberals, the more contemporary John Rawls (1921 – 2002) extends it also to some non-liberals. Rawls points out eight norms in his “realistic utopia” The Law of Peoples (1993).

The modesty of the eight principles is based on “the fact of reasonable pluralism”. To Rawls, diversity in the ways states organize their domestic life is inevitable, and so is the probability that some will be incompatible with liberal principles. There may nevertheless exist non-liberal societies which are sufficiently “decent” to be tolerated as members of equal standing in the international society. The Law of Peoples are constructed to accommodate this reasonable pluralism; to be accepted by liberal and non-liberal decent states alike.

Membership criteria and the establishment of the HRC

The HRC is neither a Kantian nor Rawlsian utopia. However, before its establishment, there were hopes that there would be traits thereof. The opinion was widely held that states sought membership of the preceding Commission on Human Rights to protect themselves against criticism regarding human rights violations. When time had come for reform, there were calls for criteria that would prevent states with poor human rights records from becoming members. Others were skeptical. They feared formal criteria would compromise the principle of sovereign equality and argued that it risked politicizing the institution further.

In the end, as suggested above, no formal membership criteria were adopted. However, the resolution establishing the Council dictates that, when electing members, states shall take into account the contribution of candidates to the promotion of human rights. There was hope that such a “soft” mechanism would sort out the worst abusers, without formally distinguishing between states. The result is mixed. On the one hand – Saudi Arabia, Burundi and China have all been members of the Council. But on the other – Iraq, Sudan and Syria have been dissuaded from running or rejected through a vote.

Universal membership and universal impact

Should the raison d’être of the HRC be judged by the success of its election-mechanism to sort out non-liberal or indecent states? Or is the universal opportunity of membership, despite the dashes of organized hypocrisy it entails, an effective mean to promote human rights?

I believe the latter. Kant’s liberal federation has not resulted in peaceful relations with states outside the federation. Similarly, exclusivity could produce negative reactions against human rights work, the integrity of which exclusivity was meant to preserve. Membership criteria may likely be perceived as politicized. A debate regarding who should be allowed to participate in human rights work risks diverting focus from the substantive human rights issues.

Inclusion, on the other hand, signals a Rawlsian tolerance for diversity and respect for equal sovereignty. The universal access to membership means that all states have the chance to participate in the peer review of other states’ human rights records in connection with the UPR. This helps to explain the UPR’s high participation rates by states undergoing review. The reviewed state knows that no other state, however powerful or developed, will be exempt from scrutiny. Moreover, the inclusionary character of the HRC gives liberal states a unique opportunity to engage with, and put pressure on, non-liberal states.

Despite all the flaws of the HRC – ranging from overlooked issues and superficial discussions to how Geneva’s price levels prevent local NGOs to participate in meetings at the Council – its universality means that human rights issues all over the world come into the spotlight. It means that when the Council speaks out against violations of human rights, it does so with the voice of the entire international community. This gives it legitimacy to engage with issues across the globe in a way an exclusive body never could.

Sara Bengtson Urwitz is a lawyer with degrees from Columbia Law School and Lund University.

Vill du skriva en text där du kommenterar, diskuterar eller kritiserar detta inlägg? Kontakta ämnesansvarig redaktör.

Editor: Gerd Johnsson-Latham

Lämna ett svar